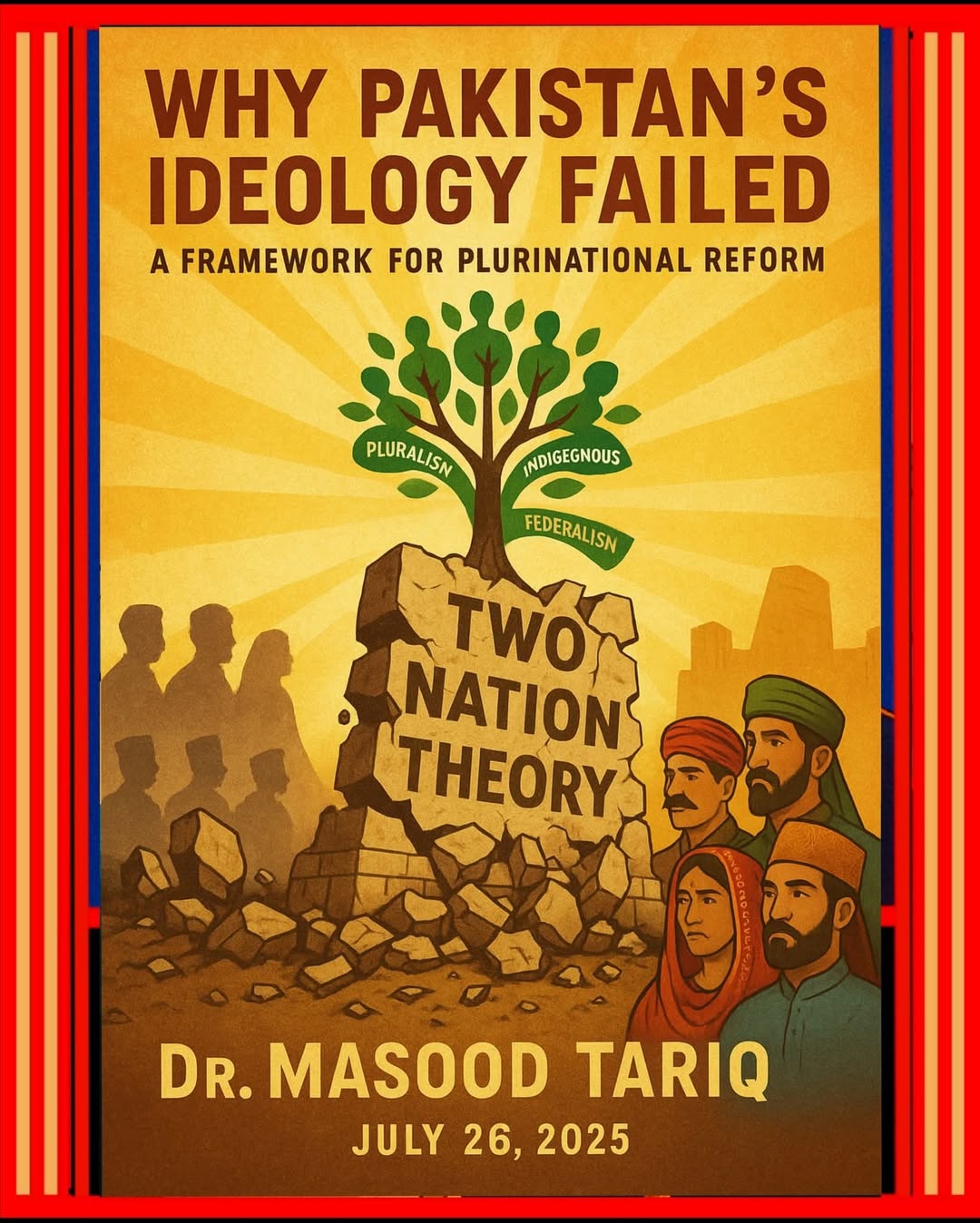

Beyond Imported Doctrines: Replacing the Uttar Pradesh Ideology with a Plurinational Framework for Pakistan

Independent Political Theorist, Karachi, Pakistan

Email: drmasoodtariq@gmail.com

Date: May 26, 2025

—

Abstract

This paper critically examines the ideological foundations of the Pakistani state, focusing on the enduring dominance of what is termed here as the “Uttar Pradesh (UP) ideology”—a worldview introduced by Urdu-speaking Muslim migrants from India’s United and Central Provinces. Rooted in Deobandi-Barelvi theology, Urdu linguistic supremacy, and Ganga-Jamuni cultural ideals, this ideology marginalized Pakistan’s indigenous nations. The article argues that a plurinational, inclusive, and indigenously rooted ideological framework is necessary for national stability, democratic cohesion, and federal restructuring. It proposes seven pillars of reform to guide Pakistan beyond this imported doctrinal legacy.

—

Introduction

Since its creation in 1947, Pakistan has struggled to develop a national ideology that reflects the historical, linguistic, and cultural realities of its diverse population. The ideological narrative that came to dominate the country’s state apparatus was largely shaped by Urdu-speaking Muslim migrants from the United and Central Provinces (UP and CP) of British India.

These migrants—politicians, religious scholars, bureaucrats, and professionals—were intellectually shaped by institutions like Aligarh University, Darul Uloom Deoband, Nadwat-ul-Ulama, and Barelvi madrassas. They brought with them an ideological worldview centered on religious homogeneity, the supremacy of Urdu, and the cultural legacy of the Ganga-Jamuna region. This worldview—termed here as the “Uttar Pradesh ideology”—sought to construct a mononational Islamic state.

However, this ideology failed to resonate with Pakistan’s indigenous nations—Punjabis, Sindhis (Sammat), Baloch, Brahui, Pashtuns, and others—who possess distinct histories, languages, spiritual traditions rooted in Sufism, and a deep civilizational link to the Indus Valley. The imposition of a singular ideological and linguistic framework not only marginalized these communities but also contributed to national fragmentation, most notably the secession of East Pakistan in 1971.

This article addresses a central question: What kind of plurinational and indigenously grounded ideological framework can replace the outdated Uttar Pradesh model to ensure Pakistan’s stability, democratic evolution, and pluralistic integrity?

—

1. The Social Composition of UP-CP Migrants

The Urdu-speaking migrants who migrated to Pakistan from the United and Central Provinces were not primarily landlords, peasants, industrialists, traders, or artisans. Rather, they were predominantly intellectuals, religious scholars, journalists, political workers, military officers, civil servants, lawyers, and professionals—forming a distinct elite class.

—

2. The Rise of the “Uttar Pradesh Ideology” in Pakistan

From the inception of Pakistan, these Urdu-speaking Muslim Indians and their descendants shaped the country’s political and administrative institutions according to their own ideological framework. This “Uttar Pradesh ideology” rested on the assumption that Pakistan was one nation—with a common religion, language, culture, and political interest.

Their religious framework was drawn from Deobandi and Barelvi interpretations of Islam, their language was Urdu, their culture was derived from Ganga-Jamuni traditions, and their political objective was to maintain their social, administrative, financial, economic and ideological dominance over Pakistan’s state system.

—

3. The Divergence of Pakistan’s Indigenous Nations

Despite a shared Islamic identity, most of Pakistan’s indigenous nations diverge sharply from this imposed ideology:

3-1. They follow spiritual traditions rooted in Sufism, distinct from the Deobandi-Barelvi theological orthodoxy.

3-2. They speak diverse languages including Punjabi, Sindhi, Pashto, Balochi, Brahui, and others.

3-3. Their cultures differ substantially from the Ganga-Jamuna culture of UP-CP migrants.

3-4. Their civilizational roots are tied to the Indus Valley, not the Gangetic plains.

3-5. They possess unique national identities and socio-political trajectories.

3-6. Their social, administrative, financial, economic and ideological interests differ markedly from those of UP-CP elites.

—

4. Rejection of the UP Ideology: The Case of East Pakistan

The most dramatic rejection of the UP-CP ideology came in 1971, when the Bengali population of East Pakistan—alienated by linguistic imposition, cultural marginalization, and political exclusion—chose to secede and establish Bangladesh.

Even today, the largest concentration of UP-CP descendants resides in Karachi—yet this community no longer represents the broader national will. However, the continued governance of Karachi—or Pakistan at large—according to the ideological preferences of this community is no longer feasible. The question arises: Can Pakistan’s governance continue to operate under the UP-CP ideological framework and Urdu language dominance?

—

5. Historical Roots of the UP-CP Ideological Project

The ideological training of Urdu-speaking elites from UP and CP had deep colonial and post-colonial institutional roots:

5-1. Fort William College, Calcutta—provided linguistic training in Urdu from the early 19th century.

5-2. Darul Uloom Deoband (1866), Nadwat-ul-Ulama (1893), and Barelvi madrassas (1904)—provided religious and ideological training rooted in the political theology of the UP-CP region.

—

6. The Absence of National Ideological Training in Pakistan

Pakistan’s indigenous nations—Punjabi, Sindhi (Sammat), Baloch, Brahui, Pashtun, Kohistani Chitrali, Swati, Gilgiti-Baltistani, and others—have never been given institutional access to define, debate, or construct their own ideological framework in their languages or on their civilizational terms.

Instead, an attempt was made to impose the UP-CP ideology across the country without accounting for historical, ethnic, and cultural diversity. As a result, Pakistan has never developed an indigenous ideological framework to guide its governance.

—

7. Key Questions Facing the Pakistani State

The current ideological vacuum poses critical national questions:

7-1. According to which ideology will Pakistan now be governed?

7-2. Can any state function effectively without a unifying ideology?

7-3. Hasn’t the continued imposition of UP-CP ideology and the Urdu language contributed to political instability, social unrest, administrative dysfunction, financial crisis …and economic decline—posing an existential threat to the state’s future stability?

—

8. A New Ideological Framework: Seven Pillars of Reform

8-1. Recognize Pakistan as a Plurinational State

Pakistan must recognize itself as a plurinational state composed of diverse nations—Punjabi, Sindhi (Sammat), Baloch, Brahui, Pashtun, Kohistani, Chitrali, Swati, Gujarati, Rajasthani, Hindustani Muhajir, and Gilgiti-Baltistani. (Kashmiri, Hindko, and Derawali are part of the Punjabi nation.)

A viable national ideology cannot be based on religious majoritarianism, Urdu uniformity, or the dominance of Ganga-Jamuni culture. It must emerge from the lived realities of all national groups.

—

8-2. Root National Ideology in Indigenous Civilizations

Instead of relying on imported frameworks from Ganga-Jamuna, Pakistan must ground its national ideology in the civilizational legacy of the Indus Valley, regional democratic traditions, and the inclusive philosophy of Sufism.

—

8-3. Establish Ideological Institutions in Every National Language

As UP-CP migrants had their ideological and linguistic institutions, similar think tanks, academies, and intellectual centers must be developed in Punjabi, Sindhi, Balochi, Brahui, Pashto, Kohistani, Chitrali, Swati, Gilgiti-Baltistani and other national languages.

These institutions should foster political education, language development, historical awareness, and leadership training rooted in indigenous perspectives.

—

8-4. Create a Permanent Forum of Pakistani Nations

A permanent Forum of Pakistani Nations should be established with representatives from each ethnonational group to:

Facilitate the drafting of a pluralistic, equitable, and federal ideological framework.

Redefine Pakistani identity beyond Urdu-Islamic mononationalism.

Propose a decentralized governance model based on mutual coexistence.

—

8-5. Promote Multilingual Federal Pluralism

Urdu may remain a link language, but all national languages must enjoy equal constitutional and administrative status in education, media, and public life.

A truly federal and multilingual ideological system is essential for unity in diversity.

—

8-6. Grant Constitutional Recognition to Nations

The constitution must recognize Pakistan’s constituent nations as equal partners, not merely administrative provinces.

Each nation should have the right to:

Control its own language, culture, education, and economy.

Be proportionally represented in federal governance structures.

—

8-7. Reform National Curriculum to Reflect Plural Histories

Pakistan’s educational curriculum must be rewritten to:

Teach the true histories of its nations.

Promote federalism, democratic coexistence, and plural nationalism.

Encourage interethnic respect, dignity, and historical understanding.

—

9. In Summary: How Can the Ideology to Run Pakistan Be Formed?

It can be formed through:

9-1. Recognize Pakistan as a Plurinational State

9-2. Root National Ideology in Indigenous Civilizations

9-3. Establish Ideological Institutions in Every National Language

9-4. Create a Permanent Forum of Pakistani Nations

9-5. Promote Multilingual Federal Pluralism

9-6. Grant Constitutional Recognition to Nations

9-7. Reform National Curriculum to Reflect Plural Histories

—-

10. Conclusion

Pakistan’s long-term unity and stability depend on its capacity to transition from an imposed and exclusionary ideology toward a truly indigenous and inclusive one. The outdated “Uttar Pradesh ideology” has served its time—and failed.

The way forward lies in recognizing Pakistan as a plurinational state, developing national ideological institutions in each language, and enacting structural reforms that reflect the country’s diverse civilizational heritage.

Only through an inclusive, decentralized, and culturally rooted ideological transformation can Pakistan fulfill the original promise of its creation—ensuring dignity, democracy, and development for all its constituent nations.

—-

Author Biography

Dr. Masood Tariq is a Karachi-based politician and political theorist. He formerly served as Senior Vice President of the Pakistan Muslim Students Federation (PMSF) Sindh, Councillor of the Municipal Corporation Hyderabad, Advisor to the Chief Minister of Sindh, and Member of the Sindh Cabinet.

His research explores South Asian geopolitics, postcolonial state formation, regional nationalism, and inter-ethnic politics, with a focus on the Punjabi question and Cold War strategic alignments.

He also writes on Pakistan’s socio-political and economic structures, analysing their structural causes and proposing policy-oriented solutions aligned with historical research and contemporary strategy.

His work aims to bridge historical scholarship and strategic analysis to inform policymaking across South Asia, Central Asia, and the Middle East.

Leave a Reply