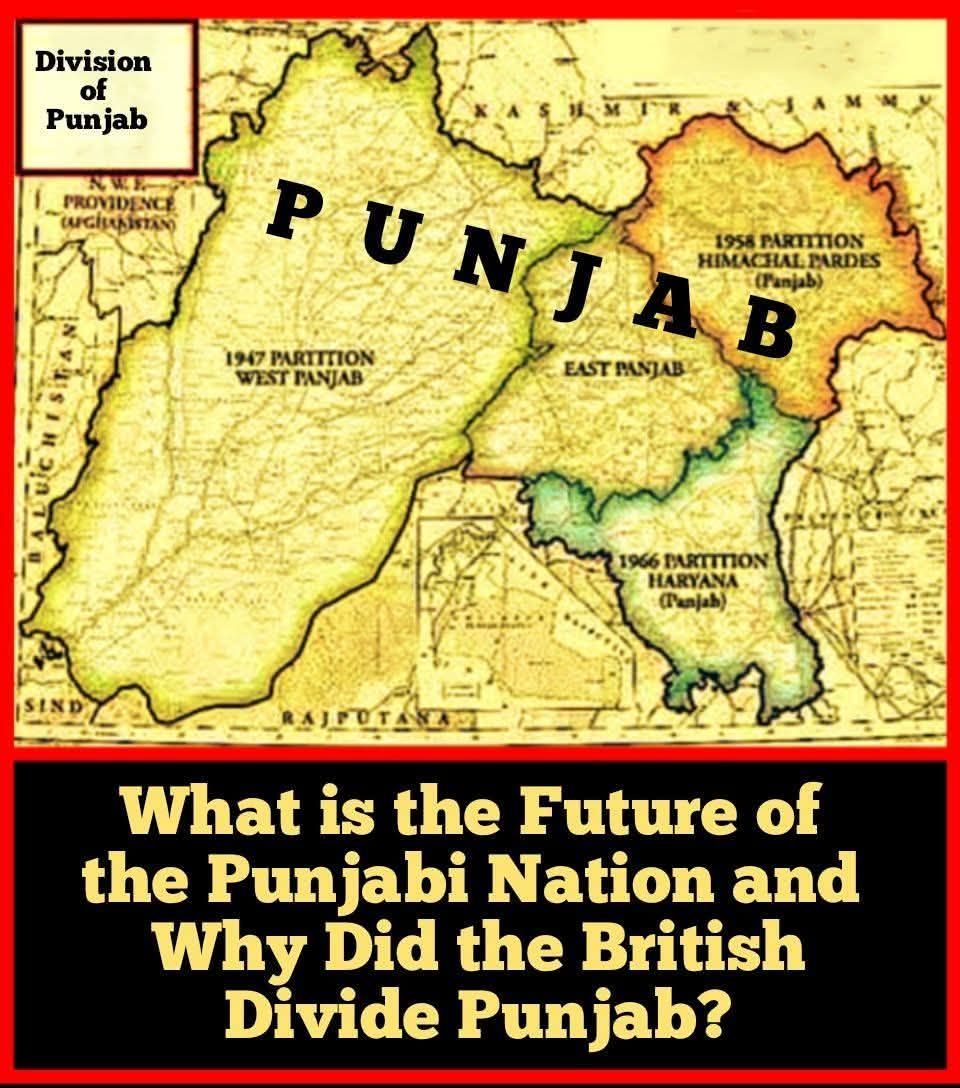

What is the Future of the Punjabi Nation and Why Did the British Divide Punjab?

Dr. Masood Tariq

Independent Political Theorist

Karachi, Pakistan drmasoodtariq@gmail.com

Date: June 22, 2025

——————————————–

Abstract:

This paper investigates the geopolitical, civilizational, and strategic motivations behind the British-engineered partition of Punjab in 1947, analyzing it as a calculated maneuver to dismantle the Punjabi Nation in alignment with emerging Anglo-American Cold War interests.

Drawing on historical data, declassified intelligence, and scholarly perspectives, it examines how the Punjabi Nation—despite being fractured—has re-emerged as a decisive geopolitical actor in the era of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), particularly through Gwadar and the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC).

The paper argues that the future of South Asian stability and the balance of power in the Indian Ocean will increasingly depend on the trajectory of the Punjabi Nation, its identity, and its political reconstitution.

——————————————–

1. Introduction:

Among the ethno-linguistic regions of British India, Punjab presented a distinctive challenge to imperial rule due to its military culture, fertile geography, and strategic location bridging Central and South Asia. Unlike other regions—such as Sindh, Balochistan, and NWFP—dominated by tribal and semi-autonomous groups, Punjab had a history of centralized governance under Maharaja Ranjit Singh.

The British only succeeded in annexing Punjab in 1849 after defeating the decaying Sikh Empire led by a ten year child ruler, Duleep Singh. The resistance of the Punjabi population during the 1857 uprising and afterward compelled the British to design elaborate mechanisms of containment—culturally, militarily, and administratively.

As Professor Ian Talbot and historian David Gilmartin have noted, the British saw Punjabis both as a martial resource and as a potential threat to colonial order (Talbot, 2007; Gilmartin, 1998). The annexation was thus followed by systematic ethnic engineering through education, military recruitment, land settlements, and the undermining of indigenous institutions.

——————————————–

2. World War II and the Anglo-American Strategic Realignment:

The conclusion of World War II heralded a shift in global power. The decline of European empires and the rise of the U.S. and USSR as superpowers realigned geopolitical priorities. The United States, promoting anti-colonial decolonization, nevertheless had strategic interests in preventing Soviet expansion into the Indian Ocean basin. Britain, under Churchill and later Attlee, sought to exit India while preserving strategic depth and influence.

Scholars such as Ayesha Jalal (2000) and Sugata Bose (2006) argue that the creation of Pakistan was not simply a response to communal pressures but part of a broader Anglo-American design to shape post-colonial geopolitics. The division of Punjab, in this context, was aimed at neutralizing a potential civilizational state that could challenge maritime and continental designs.

——————————————–

3. The Strategic Partition of Punjab: Containment of the Punjabi Nation

The British strategy, executed through the secret communications of Lord Wavell and Lord Mountbatten, involved:

i) Dissolving the secular Unionist Party, which had kept Punjabi Muslims, Hindus, and Sikhs politically united.

ii) Supporting the rise of the Muslim League in Punjab, a party dominated by elites from Uttar Pradesh and Bengal.

iii) Encouraging sectarian riots through administrative paralysis and allowing tribal militias to invade Rawalpindi and Attock in early 1947 (Khan, 2007).

iv) Using Mountbatten’s rushed boundary commission, led by Cyril Radcliffe, to arbitrarily split Punjab, ensuring massive communal displacement.

——————————————–

4. The Destruction of Punjabi Unity: A British Strategic Goal

The partition’s catastrophic consequences were not unintended collateral but the strategic outcome of imperial policy:

i) Over 2 million Punjabis killed and approximately 20 million displaced (Brass, 2003).

ii) Complete cultural severance between Sikh, Hindu, and Muslim Punjabis.

iii) A colonial legacy of mistrust, resulting in militarization and underdevelopment on both sides of the Radcliffe Line.

These outcomes, as Tan Tai Yong and Gurharpal Singh argue, fit into a larger British objective: to break the Punjabi civilizational identity and ensure neither India nor Pakistan could emerge as an independent Eurasian power (Singh & Yong, 2008).

——————————————–

5. The Cold War and the Punjabi Nation: From Resistance to Utility

During the Cold War, Punjab—particularly West Punjab—was militarized under U.S.-aligned regimes such as General Ayub Khan and General Zia-ul-Haq. Punjabi officers dominated Pakistan’s military hierarchy, enabling Pakistan to act as a frontline state during the Afghan Jihad. Zia, himself a Punjabi, called for the Islamization of the state, further diluting ethnic Punjabi identity in favor of an Islamic narrative aligned with American interests (Haqqani, 2005).

——————————————–

6. China, Gwadar, and the Return of the Punjabi Question

The rise of China as a global actor and its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), especially the CPEC, has returned Punjab to the center of global geopolitics:

i) Gwadar, in Balochistan, is accessible only through Punjab, placing the province at the heart of Chinese maritime expansion.

ii) The Sahiwal, Multan, and Lahore corridors are now critical nodes in Chinese logistics.

iii) Punjabi nationalism is resurging as Punjabi intellectuals and political groups demand cultural recognition and administrative autonomy.

Scholars such as Andrew Small (2015) argue that CPEC’s success depends heavily on Punjab’s cooperation. Meanwhile, fears in Delhi and Washington about China’s naval access through Pakistan have reignited interest in the region’s ethno-political dynamics.

——————————————–

7. Strategic Implications: Who Will Punjab Support?

With both the U.S. and China viewing Punjab as pivotal:

i) The U.S. may promote a decentralized Pakistan to weaken Chinese access.

ii) China may push for stability and unity within Punjab to secure CPEC routes.

iii) Punjabi nationalists may leverage this geopolitical competition to seek political autonomy or even confederal restructuring.

Recent Punjabi nationalist movements, such as those documented by Christine Fair (2021), have begun calling for de-Islamization of state identity and reassertion of Punjabi language and heritage.

——————————————–

8. Conclusion:

The British division of Punjab was not just a historical tragedy but a strategic act of imperial containment.

That division, which served Cold War objectives, is now being re-evaluated in light of China’s rise and America’s Indo-Pacific recalibration.

Punjab remains geographically central, demographically powerful, and culturally cohesive beneath layers of imposed division.

Whether it asserts itself as a sovereign actor, aligns with China, or re-engages with the West, the Punjabi Nation is once again at the crossroads of global history.

The question is no longer whether Punjab can rise again—but whether the world is ready for its return.

——————————————–

References:

Talbot, I. (2007). Punjab and the Raj, 1849-1947. Manohar Publishers.

Gilmartin, D. (1998). Empire and Islam: Punjab and the Making of Pakistan. University of California Press.

Jalal, A. (2000). Self and Sovereignty: Individual and Community in South Asian Islam. Routledge.

Bose, S. (2006). Modern South Asia: History, Culture, Political Economy. Routledge.

Brass, P. (2003). The Production of Hindu-Muslim Violence in Contemporary India. University of Washington Press.

Singh, G., & Yong, T. T. (2008). Partition and the Making of the Mohajir Mindset. South Asia Journal.

Haqqani, H. (2005). Pakistan: Between Mosque and Military. Carnegie Endowment.

Small, A. (2015). The China-Pakistan Axis: Asia’s New Geopolitics. Oxford University Press.

Fair, C. C. (2021). In Their Own Words: Understanding Lashkar-e-Tayyaba. Oxford University Press.

——————————————–

Author Biography

Dr. Masood Tariq is a Karachi-based politician and political theorist. He formerly served as Senior Vice President of the Pakistan Muslim Students Federation (PMSF) Sindh, Councillor of the Municipal Corporation Hyderabad, Advisor to the Chief Minister of Sindh, and Member of the Sindh Cabinet.

His research explores South Asian geopolitics, postcolonial state formation, regional nationalism, and inter-ethnic politics, with a focus on the Punjabi question and Cold War strategic alignments.

He also writes on Pakistan’s socio-political and economic structures, analysing their structural causes and proposing policy-oriented solutions aligned with historical research and contemporary strategy.

His work aims to bridge historical scholarship and strategic analysis to inform policymaking across South Asia, Central Asia, and the Middle East.

Leave a Reply