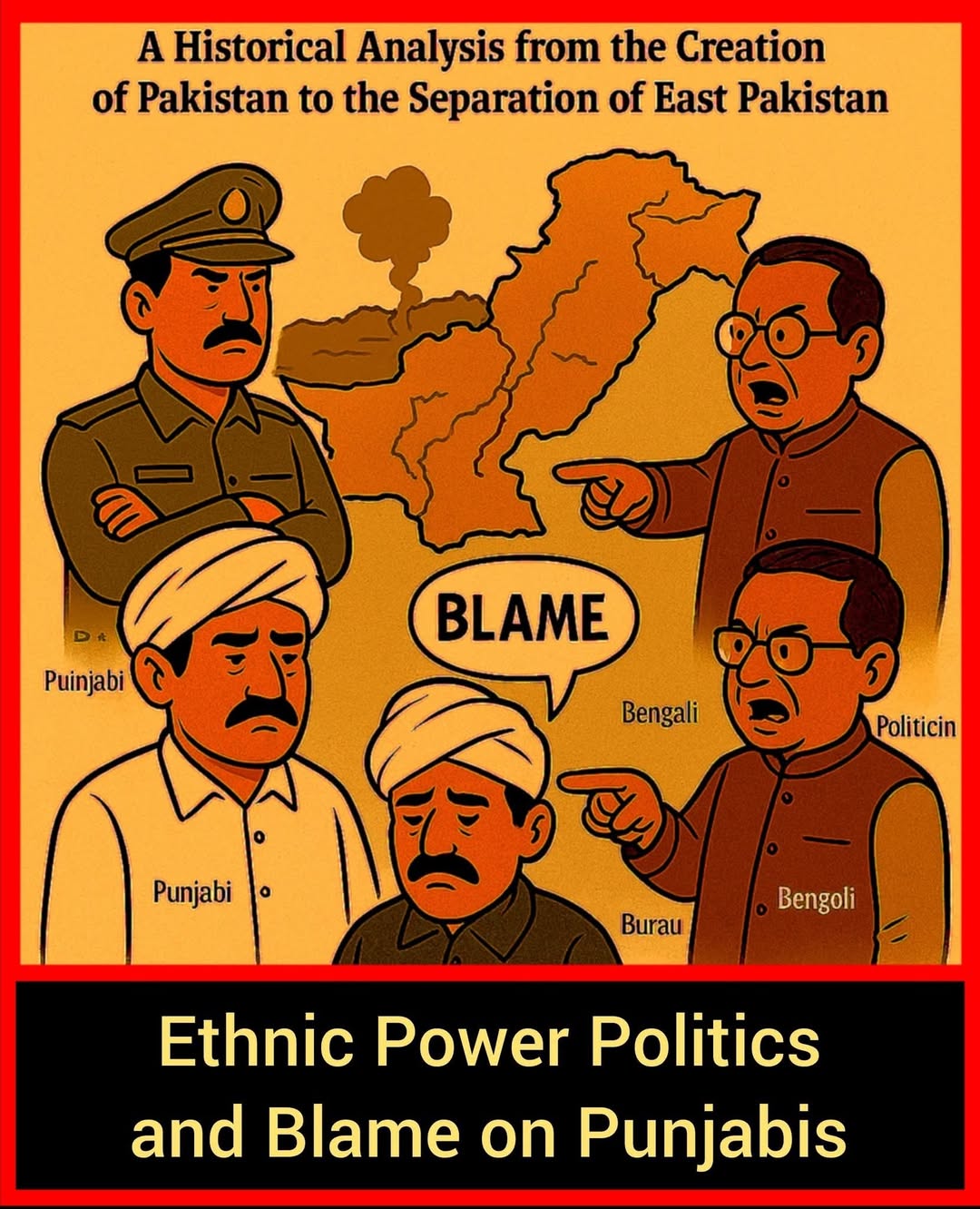

Ethnic Power Politics and the Blame on Punjabis:

A Historical Analysis from the Creation of Pakistan to the Separation of East Pakistan

Author:

Dr. Masood Tariq

Independent Political Theorist

Karachi, Pakistan drmasoodtariq@gmail.com

Date: June 5, 2025

——————————————–

Abstract:

This paper re-examines the ethnic power dynamics of Pakistan from its founding in 1947 to the secession of East Pakistan in 1971, challenging the dominant narrative that attributes authoritarianism and political inequality primarily to Punjabis.

Drawing on leadership data, institutional records, and demographic analysis, the study reveals that Pashtuns and Urdu-speaking Indian Muhajirs held disproportionate control over Pakistan’s military and bureaucracy, respectively, during the country’s formative decades. However, the Punjabi ethnic group became the principal target of public blame for state repression and political centralization.

The research highlights how a lack of Punjabi ethnic nationalism, combined with the conflation of regional residence and ethnic identity, allowed non-Punjabi elites operating from Punjab to be mistaken for representatives of the Punjabi nation. This misrepresentation, along with strategic narratives promoted by dominant ethnic groups, served to obscure the real centres of power while constructing Punjabis as convenient scapegoats.

By tracing the historical evolution of civil-military leadership, bureaucratic dominance, and ethnic discourse, the paper provides a corrective to widely held assumptions about ethnic hegemony in Pakistan and underscores the manufactured nature of anti-Punjabi sentiment in both East and West Pakistan.

——————————————–

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. Ethnic Composition of Pakistan’s Ruling Leadership (1947–1971)

3. Ethnic Duration of Rule in Pakistan (1947–1971)

4. Pathan Dominance in Military Command (1947–1972)

5. Muhajir Dominance in the Bureaucracy

6. Demographic versus Institutional Power

7. Manufactured Blame Against Punjabis

8. Conflation of Regional Origin with Ethnic Identity

9. Pashtun of NWFP Expansion under the Pretext of Patriotism

10. Pashtun of Balochistan Expansion under the Pretext of Patriotism

11. Muhajir Expansion in Sindh

12. Conclusion

——————————————–

1. Introduction

Since its formation in 1947, Pakistan has grappled with persistent ethnic tensions, political instability, and uneven power distribution among its diverse nationalities. A dominant narrative within both academic and popular discourse has long held that ethnic Punjabis monopolized the levers of power—particularly in the military and civil bureaucracy—thereby marginalizing other groups, especially Bengalis, leading to growing resentment and eventually the disintegration of the state in 1971. This narrative has shaped internal political debates, regional perceptions, and even foreign analyses of Pakistan’s civil-military imbalance.

However, this paper challenges the reductionist portrayal of Punjabis as the primary agents of authoritarianism and ethnic oppression in Pakistan’s early decades. Through a detailed analysis of political appointments, demographic representation, civil-military leadership, and state narratives between 1947 and 1971, this study argues that the actual centres of power were disproportionately occupied by Urdu-speaking Indian migrants (Muhajirs) in the civil bureaucracy and Pashtuns in the military establishment. Meanwhile, ethnic Punjabis—despite being the demographic majority in West Pakistan—were often scapegoated for the failures of centralized authoritarianism and the exclusionary policies of the state.

The absence of a coherent Punjabi nationalist consciousness allowed for a conflation between geographic residency in Punjab and ethnic Punjabi identity. This confusion enabled non-Punjabi elites based in Punjab to act in ways that were later attributed to Punjabis as a collective, thereby distorting both history and political accountability. Moreover, alliances between dominant bureaucratic-military groups and intellectuals from minority ethnic communities played a central role in reinforcing authoritarian governance—ironically while simultaneously constructing the myth of Punjabi hegemony.

By revisiting archival records, leadership timelines, institutional compositions, and the dynamics of inter-ethnic blame, this paper seeks to offer a more nuanced understanding of Pakistan’s internal power politics leading up to the secession of East Pakistan. It aims to dismantle historical myths, reassess elite complicity across ethnic lines, and contribute to a deeper discourse on the construction of ethnic blame in postcolonial state formation.

——————————————–

2. Ethnic Composition of Pakistan’s Ruling Leadership (1947–1971)

The total number of Heads of Government of Pakistan from the creation of Pakistan till the creation of Bangladesh was 10:

Urdu-speaking Heads of Government = 4

Pashtun Heads of Government = 2

Bengali Heads of Government = 2

Punjabi Heads of Government = 2

Following were the Heads of Government from the creation of Pakistan till the creation of Bangladesh:

i). Nawabzada Liaquat Ali Khan

(Nominated Prime Minister)

15 August 1947 – 16 October 1951

(Urdu-speaking from Sindh)

ii). Khawaja Nazimuddin

(Nominated Prime Minister)

17 October 1951 – 17 April 1953

(Urdu-speaking from East Bengal)

iii). Muhammad Ali Bogra

(Nominated Prime Minister)

17 April 1953 – 11 August 1955

(Bengali-speaking from East Bengal)

iv). Chaudhary Muhammad Ali

(Elected Prime Minister)

12 August 1955 – 12 September 1956

(Punjabi-speaking from Punjab)

v). Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy

(Elected Prime Minister)

12 September 1956 – 16 October 1957

(Bengali-speaking from East Bengal)

vi). Ibrahim Ismail Chundrigar

(Elected Prime Minister)

17 October 1957 – 16 December 1957

(Urdu-speaking from Sindh)

vii). Malik Feroz Khan Noon

(Elected Prime Minister)

16 December 1957 – 7 October 1958

(Punjabi-speaking from Punjab)

viii). General Iskander Mirza

(Martial Law Administrator – President)

7 October 1958 – 27 October 1958

(Urdu-speaking from East Bengal)

ix). Ayub Khan

(Martial Law Administrator – President)

27 October 1958 – 25 March 1969

(Pashto-speaking from Khyber Pakhtunkhwa)

x). Yahya Khan

(Martial Law Administrator – President)

25 March 1969 – 20 December 1971

(Pashto-speaking from Punjab)

——————————————–

3. Ethnic Duration of Rule in Pakistan (1947–1971)

Pakistan came into existence on 15 August 1947, and East Pakistan was separated on 20 December 1971, after 24 years, 4 months, and 6 days.

Duration of rule by Muhajir, Pashtun, Bengali, and Punjabi from the creation of Pakistan till the creation of Bangladesh:

Pashtun ruled 4,805 days out of 8,894 = 54.02%

Muhajir ruled 2,154 days out of 8,894 = 24.29%

Bengali ruled 1,244 days out of 8,894 = 13.99%

Punjabi ruled 693 days out of 8,894 = 7.79%

——————————————–

4. Pathan Dominance in Military Command (1947–1972)

From independence until the separation of East Pakistan, the Pakistan Army was under near-total control of British officers and later Pathan generals. The chronological list of Commanders-in-Chief of the Pakistan Army is as follows:

i). General Frank Messervy (British):

Served from August 15, 1947, to February 10, 1948.

ii). General Douglas Gracey (British):

Served from February 11, 1948, to January 16, 1951.

iii). General Ayub Khan (Pathan):

First Pakistani C-in-C and later President. Instituted Pakistan’s first martial law in 1958.

Held power from January 1951 to October 1966 as Commanders-in-Chief of the Pakistan Army.

Held power from October 27, 1958 to March 25, 1969 as President of Pakistan.

iv). General Musa Khan (Pathan):

Held office from 1958 to 1966, including during the 1965 war.

v). General Yahya Khan (Pathan):

Held power from 1966–1971, led the country during the 1971 civil war.

vi). General Gul Hasan Khan (Pathan):

Brief tenure from December 1971 to March 1972.

The first Punjabi to become head of the Pakistan Army was General Tikka Khan in 1972, after the secession of East Pakistan and the removal of many Pathan generals.

——————————————–

5. Muhajir Dominance in the Bureaucracy

On the other hand, Pakistan’s bureaucracy remained under the dominance of Indian Muhajirs. An analysis of senior bureaucratic positions in 1951 confirms this:

Top 91 Government Jobs:

Urdu-speaking Muhajirs: 33

Punjabis: 40

Pathans (Pashtuns): 3

Bengalis: 5

Sindhis: 1

Foreigners: 9

Breakdown of 13 Secretaries:

Urdu-speaking Muhajirs: 5

Punjabis: 5

Others (Pathans, Foreigners): 3

Joint Secretaries (Total: 19):

Urdu-speaking Muhajirs: 9

Punjabis: 7

Others: 3

Deputy Secretaries (Total: 59):

Urdu-speaking Muhajirs: 19

Punjabis: 28

Others: 12

This data shows that Indian Muhajirs held 50–60% of high-level federal positions—far above their 3% share of Pakistan’s population.

——————————————–

6. Demographic versus Institutional Power

In Pakistan, the populations of Pathans and Indian Muhajirs have always been relatively small. Initially, Bengalis were the majority; now, Punjabis are the largest group. In a democratic system, power resides with the majority. Therefore, Bengalis and Punjabis initially benefited from democracy; now, it is Punjabis and Sindhis.

Due to their smaller population sizes, Pathans and Indian Muhajirs have never truly benefited from democracy—neither in the past nor today. However, because of their strong sense of nationalism, and the absence of such nationalism among Punjabis:

i). Pathan and Indian Muhajir intellectuals and politicians, in collaboration with the military and bureaucracy (dominated by their own ethnic groups), sustained dictatorship in Pakistan.

ii). These same Pathan and Muhajir intellectuals and politicians blamed the Punjabi military and bureaucracy for dictatorship in Pakistan, thus creating the false impression that Punjabis were responsible for military rule.

——————————————–

7. Manufactured Blame Against Punjabis

Even though East Pakistan’s population was larger than West Pakistan’s, Bengalis were not given proportional representation in federal government institutions. Even at the provincial level, instead of employing Bengalis in East Pakistan, Biharis were imposed on them.

Furthermore, when Muhammad Ali Jinnah declared in 1948 in Dhaka that Urdu would be Pakistan’s national language—and Prime Minister Liaquat Ali Khan enforced this—those leading the Bengali language and nationalist movement were persecuted.

Consequently, Punjabis were branded by these movements as dictators, usurpers, exploiters of the Bengali nation, and looters of East Pakistan—and were widely vilified.

One key reason behind Bengali resentment toward Punjabis was this failure to distinguish between those merely residing in Punjab and those who were actual members of the Punjabi nation. Due to the absence of Punjabi nationalism, no such distinction was made.

Because Punjabis considered everyone living in Punjab to be Punjabi:

i). Non-Punjabis living in Punjab ruled Punjab and Pakistan—rather than the Punjabi nation itself.

ii). The actions of these non-Punjabis from Punjab were blamed on Punjabis as a whole.

——————————————–

8. Conflation of Regional Origin with Ethnic Identity

The absence of Punjabi nationalism led to a conflation of geographic residence and ethnic identity. Non-Punjabis residing in Punjab were seen as Punjabi, and their actions were blamed on ethnic Punjabis. For instance:

a) Pakistan’s first Prime Minister, Liaquat Ali Khan—an Urdu-speaking Indian Muhajir from Karnal—was labelled a Punjabi.

b) Pakistan’s third Governor-General, Ghulam Muhammad—a Pathan born in Lahore—was labelled a Punjabi.

c) Pakistan’s first Martial Law Administrator and President, Ayub Khan—a Pathan from Haripur, Hazara—was labelled a Punjabi.

d) Pakistan’s second Martial Law Administrator and President, Yahya Khan—a Pathan from Chakwal—was labelled a Punjabi.

e) The Commander of the Eastern Command of the Pakistan Army and Governor of East Pakistan and the man who surrendered to Sikh Punjabi General Arora in 1971—Lieutenant General Abdullah Khan Niazi, a Pathan from Mianwali—was labelled a Punjabi.

——————————————–

9. Pashtun of NWFP Expansion under the Pretext of Patriotism

Additionally, the “Azad Pashtunistan” movement led by Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan was covertly encouraged to reinforce the idea that it was Pathan military officers and NWFP residents who crushed the anti-Pakistan movement. The implication was that had they not done so, an independent Pashtunistan would have emerged. As a result:

a) Punjabis vilified pro-Pashtunistan Pashtuns while admiring those in the military and NWFP who opposed it. They welcomed such Pashtuns to settle and do business in Punjab and supported their growing recruitment in the military.

b) With growing Pashtun influence, Pashtuns began to occupy lands belonging to Hindko-speaking Punjabis in NWFP (now Khyber Pakhtunkhwa), secure government jobs, expand political influence and even move into western Punjab.

c) Meanwhile, pro-Pashtunistan leaders portrayed Punjabis as oppressors and exploiters of Pashtuns and NWFP, fueling anti-Punjabi sentiment.

——————————————–

10. Pashtun of Balochistan Expansion under the Pretext of Patriotism

Similarly, the “Azad Balochistan” movement led by Khair Bakhsh Marri was encouraged to imply that it was Pathan officers in the army and Pashtun residents of Balochistan who prevented Balochistan’s secession. As a result:

a) Punjabis condemned pro-Baloch independence figures while praising Pashtun military officers and local Pashtuns who opposed the movement. They supported Pashtun migration to Punjab and their recruitment into the armed forces.

b) As Pashtun influence grew, they occupied lands belonging to Baloch and Brahui tribes, secured key positions, expanded political clout, and took over vast areas of Balochistan.

c) Meanwhile, Baloch nationalists depicted Punjabis as authoritarian and exploitative looters of Balochistan, intensifying public resentment against Punjabis.

——————————————–

11. Muhajir Expansion in Sindh

Finally, in Sindh, the “Sindhi Nationalist” movement was covertly encouraged similarly to show that it was the Pathan in the army, the Indian Muhajirs in the bureaucracy, and urban Muhajirs in Sindh who had crushed the anti-Pakistan movement. The implication being that without their efforts, Sindhudesh would have become a reality. As a result:

a) Punjabis kept cursing pro-Sindhi Nationalism Sindhis while praising anti-Sindhi Nationalism Pathans, the Indian Muhajir bureaucracy, and urban Muhajirs in Sindh. They helped them settle and start businesses in Punjab and were happy to see more Muhajirs recruited in the army and bureaucracy.

b) Due to the influence of Indian Muhajirs in the government and bureaucracy, they gradually occupied land belonging to Sindhis, secured government jobs, expanded their political control, and completely dominated urban areas—especially Karachi, Hyderabad, Sukkur, Nawabshah, Mirpurkhas cities.

c) At the same time, Sindhi nationalist leaders used their platforms to portray Punjabis as dictators, usurpers, exploiters, and looters of Sindh—thus stoking hatred toward the Punjabi people.

——————————————–

12. Conclusion

The dominant historical narrative that attributes the failure of Pakistan’s early state-building project—and the eventual secession of East Pakistan—to Punjabi dominance in national institutions does not withstand critical scrutiny. As this paper has demonstrated, the actual composition of power from 1947 to 1971 reveals a far more complex ethnic matrix in which Urdu-speaking Indian Muhajir civil bureaucrats and Pashtun military leaders played leading roles in shaping, enforcing, and defending the centralized, unitary state structure that ultimately alienated East Pakistan.

Punjabis, despite forming the largest ethnic group in West Pakistan, did not exhibit a cohesive ethnic or political identity during the early decades of independence. Instead, the Punjab-based institutions were often staffed and led by non-Punjabi elites, particularly Urdu-speaking Indian Muhajir who dominated the civil services and policymaking circles. The military, although associated with Punjab due to recruitment patterns, was disproportionately led by officers of Pashtun origin, many of whom held key decision-making positions during crucial junctures in the state’s evolution.

The myth of Punjabi hegemony, therefore, served both as a political deflection and as an ideological construct that allowed various ethnic elites to externalize blame and evade responsibility for policies they themselves co-authored and implemented. The collapse of East Pakistan in 1971 was not simply a reaction to Punjabi domination, but rather the result of systemic exclusion, authoritarianism, and a refusal by ruling elites across ethnic lines to accommodate the federal and linguistic aspirations of the Bengali majority.

Understanding the misrepresentation of Punjabi power is not merely a matter of historical correction—it is essential for informing contemporary debates on interethnic relations, federalism, and national cohesion in Pakistan. Only by disentangling fact from political fiction can the country move toward a more inclusive and honest reckoning with its past and, potentially, a more stable and equitable future.

——————————————–

References:

Ansari, S. (2016). Pakistan’s 1951 Census: State-Building in Post-Partition Sindh. South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies, 39(3), 1–20.

Jaffrelot, C. (2002). Pakistan: Nationalism Without a Nation? Zed Books.

Paracha, N. F. (2014, April 20). The evolution of Mohajir’s politics and identity. Dawn.

Visweswaran, K. (2011). Perspectives on Modern South Asia: A Reader in Culture, History, and Representation. John Wiley & Sons.

Bahadur, K. (1998). Democracy in Pakistan: Crises and Conflicts. Har-Anand Publications.

Zakaria, R. (2004). The Man Who Divided India: An Insight Into Jinnah’s Leadership and Its Aftermath. Popular Prakashan.

Sareen, S., & Shah, K. M. (2020). The Mohajir: Identity and politics in multiethnic Pakistan. Observer Research Foundation.

Bhattacharya, S. (2015). Pakistan’s Ethnic Entanglement. Institute for Conflict Management.

Alavi, H. (1988). Pakistan and Islam: Ethnicity and Ideology. In F. Halliday & H. Alavi (Eds.), State and Ideology in the Middle East and Pakistan (pp. 64–111). Macmillan.

GlobalSecurity.org. (n.d.). Chief of Army Staff (COAS) – Military. Retrieved from https://www.globalsecurity.org/…/pakistan/army-coas.htm

——————————————–

Author Biography

Dr. Masood Tariq is a Karachi-based politician and political theorist. He formerly served as Senior Vice President of the Pakistan Muslim Students Federation (PMSF) Sindh, Councillor of the Municipal Corporation Hyderabad, Advisor to the Chief Minister of Sindh, and Member of the Sindh Cabinet.

His research explores South Asian geopolitics, postcolonial state formation, regional nationalism, and inter-ethnic politics, with a focus on the Punjabi question and Cold War strategic alignments.

He also writes on Pakistan’s socio-political and economic structures, analysing their structural causes and proposing policy-oriented solutions aligned with historical research and contemporary strategy.

His work aims to bridge historical scholarship and strategic analysis to inform policymaking across South Asia, Central Asia, and the Middle East.

Leave a Reply